On 19 January 2017, during the New Year’s reception hosted by NRK (the Dutch Plastic and Rubber Branch) and Plastics Europe Netherlands, the “Rethink” plan was launched: a fresh look at plastic and rubber in response to mounting political and social criticism and controversy of how these materials are managed in the chain. This article makes clear why business-as-usual is no longer an option – and why there is a need for a proactive industry that “Rethinks” and “Reinvents”.

“Plastic is Fantastic”

Plastic is incredibly important to our economy. Production rose twentyfold worldwide between 1960 and 2014. In Europe, more than 60,000 companies in the plastics industry employ 1.5 million people and generate annual turnover of €340 billion. Plastic is extremely functional and versatile. Plastic packaging – which accounts for nearly 40% of plastics market demand – is adept at protecting its contents, but also light. As a result, its use creates CO2 savings in the value chain. You cannot avoid plastic. The most common polymers like PE, PP and PET are found in many products across pretty well all sectors of the economy. And, of course, plastic can be recycled – or the energy from it recovered. All this is true, but not the whole story.

Plastic: perhaps the worst example of the linear economy?

Plastic arouses a lot of emotion, among citizens. There are many growing concerns clustered around the fundamental fear that the world faces a daunting waste management problem. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation states in “The New Plastic Economy. Rethinking the future of plastics (2017)” that by 2050, if we do not change course, there will be more plastic than fish in the sea. Such images jolt people into action.

Plastic is made from scarce resources

Plastic is over 90% fossil fuel. In contrast, recycled and bio-based plastics together account for less than 10% of total plastic production in 2013 (The New Plastics Economy: rethinking the future of plastics). The first thing that comes to mind with fossil fuels is that they are finite, and their use causes release of greenhouse gases. What does that mean for plastic?

Plastic has an undeniable waste problem

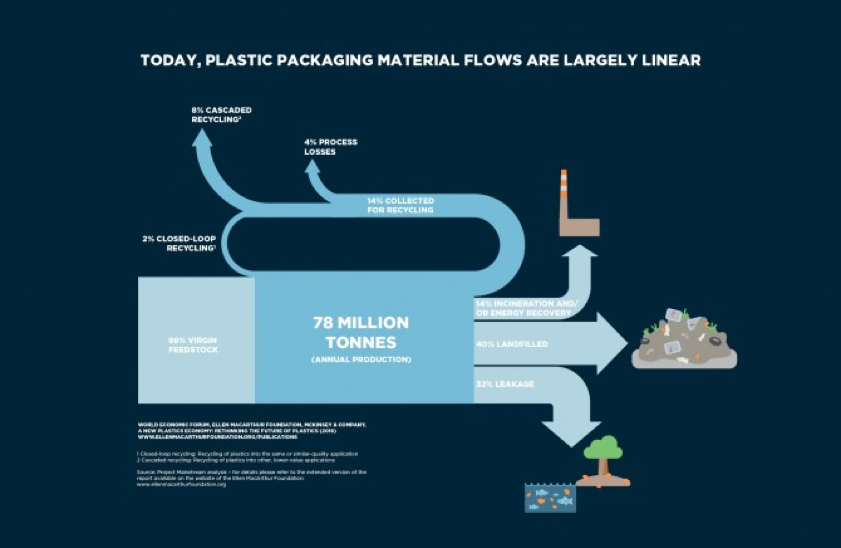

Plastic Europe tracked the EU’s recycling performance between 2006 and 2014. It reports a 64% increase in the household plastics recycling rate – and a 38% decrease in plastics dumping. That sounds good. In absolute terms, however, more plastics are landfilled or incinerated than recycled. Too much plastic ends up as litter. That image lingers longer in the memory than plastics’ useful properties. And even where there is recycling, it is strongly associated with down-cycling: whereby after just one cycle, all you can do is incinerate it. Worldwide, the numbers for plastic packaging are downright shocking: 40% is landfilled; 14% is incinerated; and 32% goes missing in the ecosystem. Only 14% is collected for recycling – and the true “closed loop” recycling rate is only 2%.Of course, in my country Holland, we do much better. But with such statistics you cannot hide behind the branch; point to your own little role in the global supply chain; and shift responsibility to others, further along the chain. If plastic is everywhere and in everything, you should also take responsibility for the entire chain.

Figure 1: Global plastic packaging flows in 2013 (The new plastics economy: rethinking the future of plastics (2016))

Coincidence? Simultaneously, while the branch’s annual meeting was being held, the movie “A Plastic Ocean” premiered, as part of a worldwide campaign in Pathé Tuschinski in Amsterdam. Highlighting pollution of the oceans with plastic, the phrase “Plastic Soup” raises enormous emotion worldwide – and this sentiment, not surprisingly, translates into general opposition to plastics. These perceptions are a fact; one that the industry must learn to live with.

Concerns about harmful substances

The plastics industry needs also to address concerns about the harmful substances that plastics can contain, such as plasticisers or stabilisers with toxic properties. These have been or will be phased out in new products, but as “legacy” components they continue to circulate in our system. The debate is complex and focuses on mitigating risks and exposure. Because plastic is ‘everywhere’ and in ‘everything’, it is making families rightly concerned – just as we are also concerned about baby milk scandals in China; the risks of nuclear energy after Fukushima; or our children who play football on synthetic fields with rubber granules that might contain carcinogenic substances.

Guilt Free Consumption

Citizens – often the customers of your customers – increasingly want what we so beautifully call “guilt-free consumption”. If we want to buy something we can assume that the producer does not use child labour and that there are no risks to the environment and health in the chain. We have in the Volkswagen emission scandal seen how quickly the value of a business can evaporate thanks to unethical behaviour. Political and economic sentiment has also been rapidly changing, in recent years. In 2015, 174 countries signed the Paris climate agreement, and noted the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Multinationals set increasingly sustainable targets like zero-waste-to-landfill, zero energy production sites, or – to keep it in plastic – a strategy focused on products or packaging sourced from plastic that is 100% bio-based, circular or recycled.

Business as usual is no longer an option

There is an urgent need to design, produce, consume, but also to communicate better. A reactive plastics industry will see its sphere of influence and sales decline. “Better safe than sorry” regulatory policies may come sooner than we think. Free plastic bags are gone (good that the bags are finally being appreciated?). Conceivable that the plastic water bottle could be the next victim? The industry will also have to work together, when it comes to a meaningful future policy concerning hazardous substances and “legacy” components. The discussions are supranational and call for cooperation between national, EU industry associations and governments on complex regulations for waste and chemicals alike.

The future is circular

The Netherlands government’s ambition is to have a 50% lower consumption of primary raw materials – such as minerals, metals and fossil fuels – by 2030. By 2050 it wants to go completely circular. In this massive challenge, plastic is regarded as one of the five value chains with the highest priority.

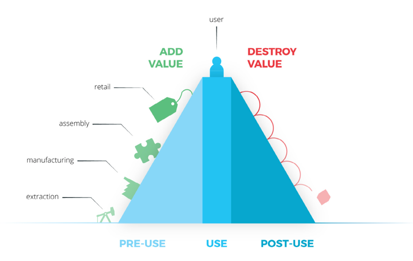

The Circular Value Hill concept illustrates that it takes effort to give products such as plastic value. It’s like pushing a ball up the hill. In a circular economy, you want to maintain the value (with the embedded energy, materials, creativity and functionality) for as long as possible, and hold on to as high a level as possible. In the case of plastic rolls the post-use value is not the same as if it were on top of the hill. Globally, 40% are at the foot of the mountain and 32% leak away into the ecosystem. The bit of value we hold through recycling is very low on the hill.

Figure 2: The Circular Value Hill concept (Sustainable Finance Lab, Circle Economy, Nuovalente, TUDelft, and het Groene Brein)

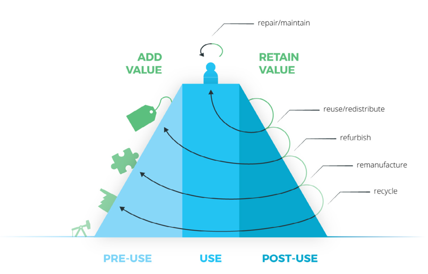

The art, through good design and collaboration with partners, is to ensure that plastic remains as long and circling as high as possible; as can be seen in the “Retain value” loops in the “Value Hill”.

Radical new approach

There is still a world to win through better design of plastics, says a recent report from the Ellen MacArthur. At least 70% of plastic packaging worldwide could be reused or recycled, whereas the actual figure is only 14%. The report proposes a radical new approach. “Rethinking the global plastics economy requires an ambitious, systemic approach. This means collaborating across silos, and moving in a common direction to deliver impact at scale. It requires overcoming the dizzying complexity of materials and the embedded fragmentation of processes. It’s about thinking of an interdependent system rather than a series of isolated parts. It means being open to new ideas and experiments, to identify those innovations that can scale to shift the market.” It further recommends to create an effective after-use plastics economy; to drastically reduce the leakage of plastics into natural systems and to decouple plastics from fossil feedstocks.

Technological developments are stronger than ever, even in plastics. For almost any polymer made from oil, there has been a bio-based variant; and improved chemical recycling increasingly provides the ability to connect high-quality chains. The developments could unfold just as they have with solar cells. From a circular smart policy may come an economic tipping point, not too far into the future. There are threats but also opportunities to create value and to preserve the sector by working on new circular business models, such as virtualisation, dematerialisation and service models based on “from ownership to use.”

Rethink and Reinvent

There is a world to win for the plastics industry. After all, it is a material with amazing properties. The increasingly critical trend afflicting plastic’s image will be broken. Passivity almost always leads to regulations that turn out badly for a sleeping industry. The plastics industry can play a leading role in assessing their socially important product value. This goes beyond technical innovation and beyond the first instinct of the branch to prove with facts and figures. It calls for an industry which, like its product, is in the thick of society, is empathetic and proactively looking for solutions. Turn the threat into an opportunity by setting the utility, safety, durability, use, reuse, recycling and innovation of the plastic products prominent on the agenda. Furthermore, demonstrate how the industry contributes to the realisation of CO2 reduction and a circular economy. The momentum is there: in mid-2017, a transition agenda for plastics will be set in the Netherlands; and submissions are open for this year’s draft “EU Strategy Roadmap on Plastics in a Circular Economy”, to be finalised at the end of 2017.

A (limited) Dutch version of this article has been posted on February, 1, 2017 in the Magazine Kunststof & Rubber p.18-20